The Palau National Marine Sanctuary and Palau’s Shark Sanctuary

Within the Indo-Pacific, Palau is recognized as a leader in marine conservation. In 2009, former President Toribiong declared Palau’s waters as the world’s first shark sanctuary, but the shark sanctuary was never signed into law. The Shark Haven Act (Senate Bill #8-105), proposed in 2009, was not adopted. A 2003 Palau law (RPPL 6-36) banning the use of wire traces and the retention of sharks, including their fins, by foreign fishing vessels, still had protective effects for sharks, especially those caught by longline gear.

Within the Indo-Pacific, Palau is recognized as a leader in marine conservation. In 2009, former President Toribiong declared Palau’s waters as the world’s first shark sanctuary, but the shark sanctuary was never signed into law. The Shark Haven Act (Senate Bill #8-105), proposed in 2009, was not adopted. A 2003 Palau law (RPPL 6-36) banning the use of wire traces and the retention of sharks, including their fins, by foreign fishing vessels, still had protective effects for sharks, especially those caught by longline gear.

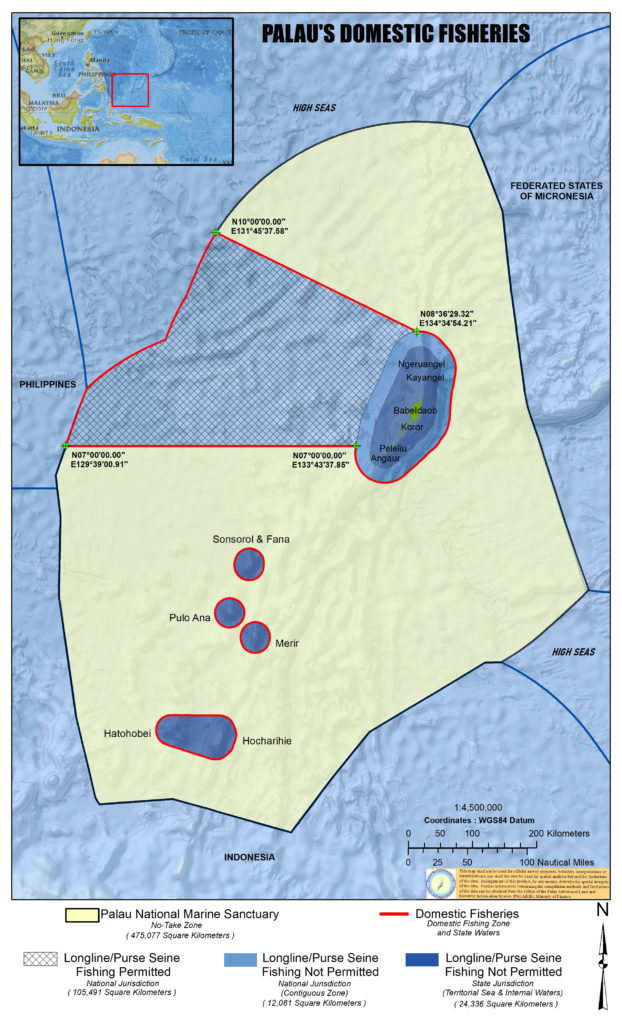

In 2015, the Olbiil Era Kelulau (Palau National Congress) passed the Palau National Marine Sanctuary (PNMS) Act (RPPL 9-49). It established 80% (500,000 km²) of Palau’s EEZ as a no-take reserve and the remaining 20% as a domestic fishing zone (DFZ) where fishing by local, foreign or chartered licensed fishing vessels is allowed (RPPL 9-49 ; amended by RPPL 10-35). The original PNMS Act included a provision that prohibited any person to fish for, remove fins or possess any part of any shark within Palau’s waters. Another law related to reef fish exports (RPPL 9-50) annulled the PNMS Act’s blanket shark protections and reef sharks within Palau’s coastal waters are currently not legally protected from injury, mutilation or taking through fishing or other means.