Measuring Water Temperature: The need to dig below the surface

When considering the actual temperatures impacting the marine environment, it is important to remember that the shallow sea surface, if reasonably calm, during the day can become much warmer than the underlying water just 5-10 cm below. This “skin” temperature can often be several degrees C higher than the “bulk” water just below it. Unfortunately satellites used for measuring remote sea surface temperature (SST) measurements “see” only the skin layer of the ocean and typically try to get around this problem by taking temperature measurements before dawn. Unless there is vertical mixing of the skin and bulk water below it, that SST value may not be the same as the temperature even 1 m below where reefs occur. It is incumbent on the researcher, whenever possible, to actually measure the water temperature on reefs at various depths with accurate in situ instruments to check for any skin temperature errors from satellite SST data.

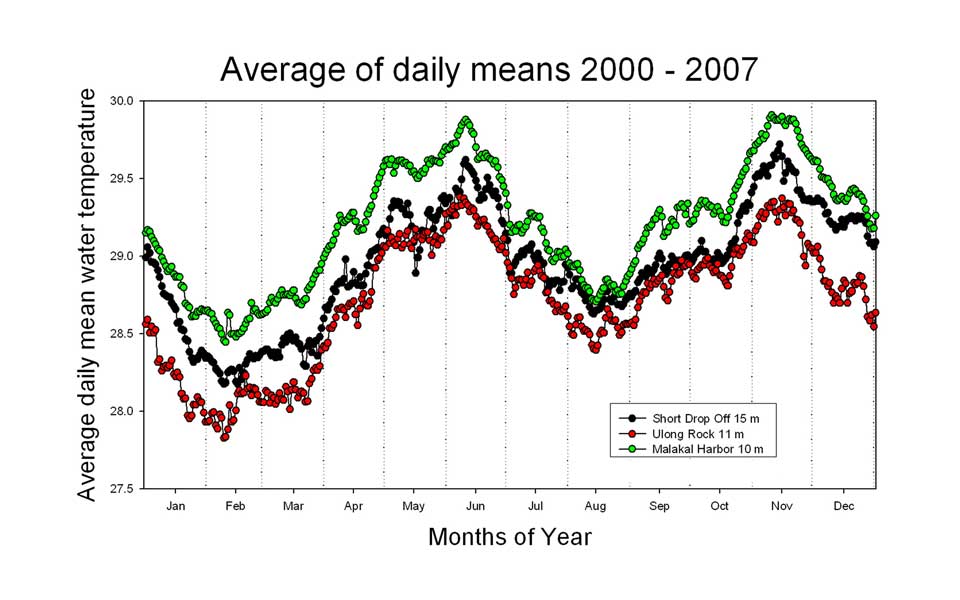

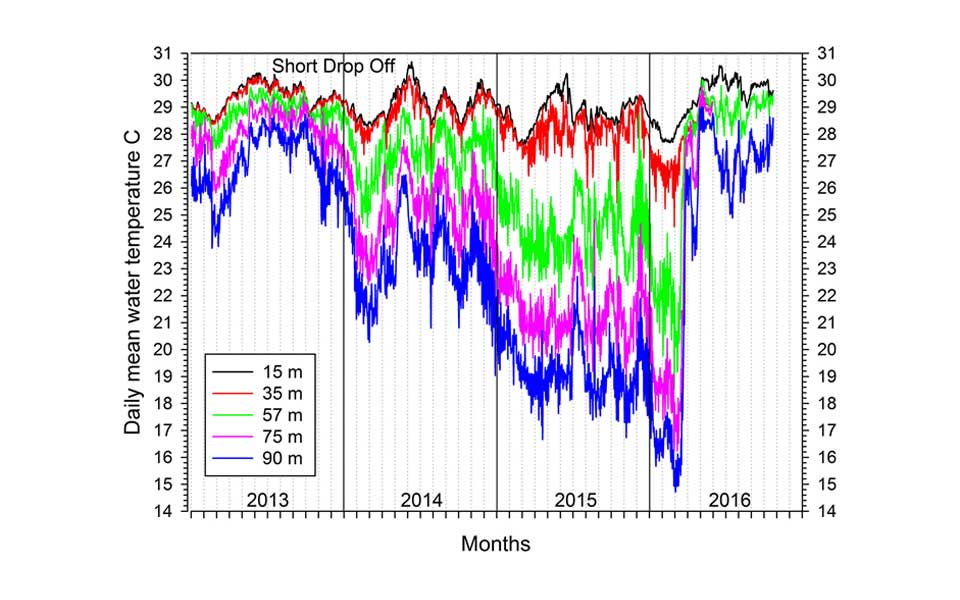

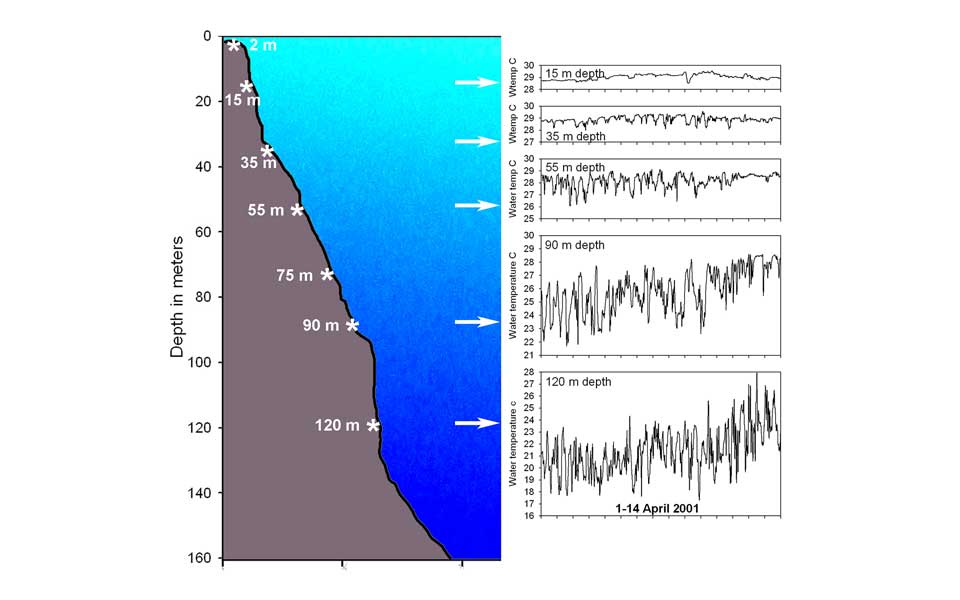

The thermal structure of the water column below the surface and its heat content cannot be accurately measured via satellite remote sensing. It is necessary to place instruments at various depths or have some type of profiling instrument (see Ocean Observations). In Palau we place recording thermographs at selected depths along the reef profile by diving, leave them to collect data and then recover later and download. Such a deployment of thermographs is called a “vertical array”, each unit recording at its given depth on the same sampling schedule (up to once per minute). The disadvantage of such a system is that you have to find and recover the instruments to get any data, but such arrays can be set up relatively cheaply. A publication in the journal of The Oceanography Society by Pat Colin provides a 20 year overview of seawater temperature on the outer reefs of Palau. Thermographs can also be set up on a mooring, distributed along a line with a float at the top and a heavy weight at the bottom. This has disadvantages in that the mooring can break and float away or the float can fail and then the array sinks to the bottom. Currents also bend the mooring downward, so the depth of each thermograph can change often, producing variable data not at a consistent depth. The array placed along the reef is the best way to get solid data over a period of many months to years. Recent work in Palau with Travis Schramek, Scripps Inst. of Oceanography, in Geophysical Research Letters, has shown that mean sea level (MSL) is a good proxy for heat content of the upper ocean where reefs occur. MSL is a value that can be measured either by satellite or via a tide gauge located near the reefs of interest.